review of resistance and hope, edited by alice wong

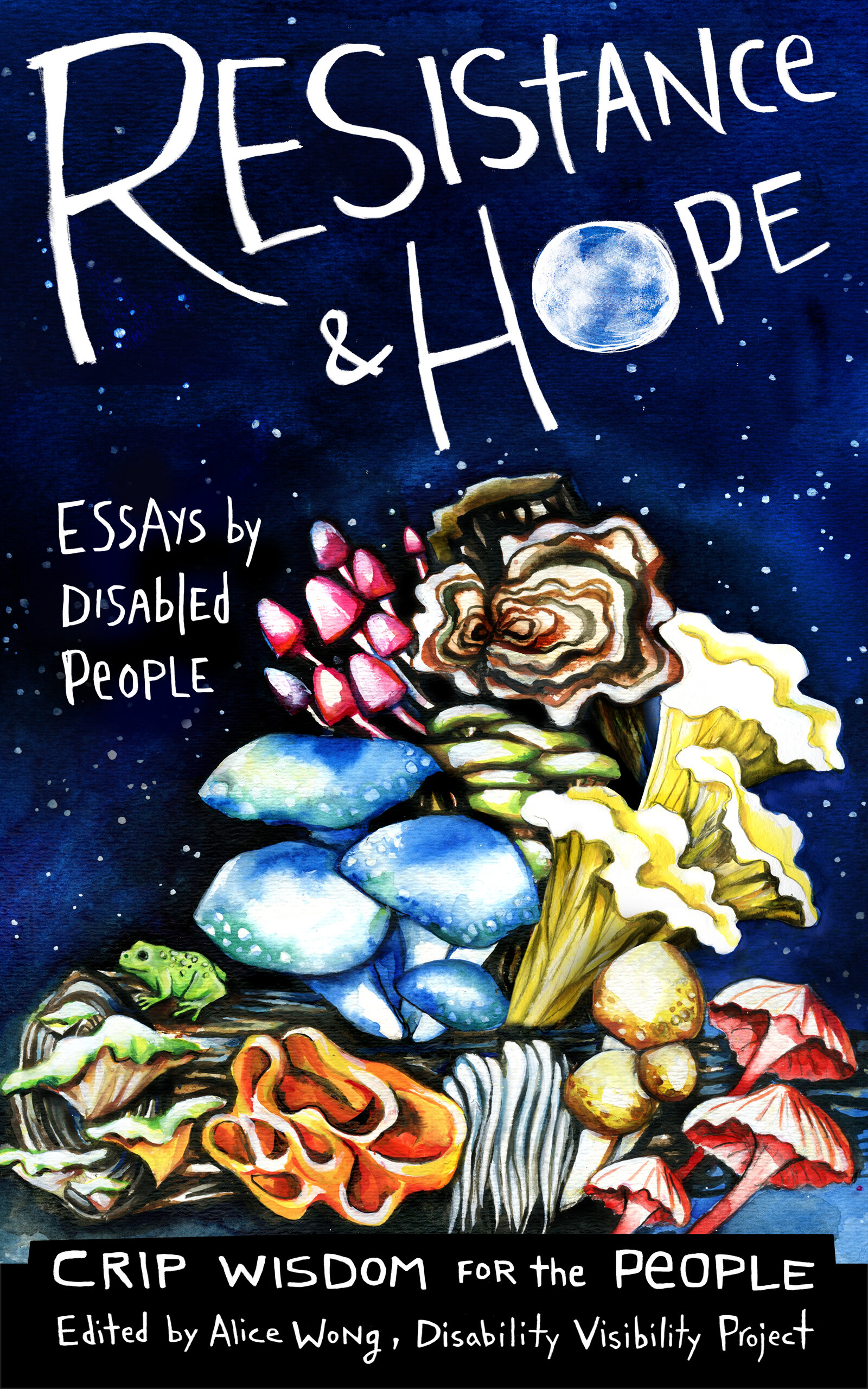

[Image Description: 'Resistance and Hope' in white font on a dark blue background. The 'O' of hope is a moon. Underneath the text are blue, pink, yellow and brown mushrooms growing off a log. Left of the mushrooms reads 'Essays by Disabled People'. Below reads 'Crip Wisdom for the People, Edited by Alice Wong, Disability Visibility Project'.]

Alice Wong is absolutely badass. Having written for just about every notable news and media platform that exists, serving on Barack Obama’s National Council on Disability, and starting projects such as the Disability Visibility Project among a multitude of other achievements, she blesses absolutely everything she touches with her commitment to accessibility and justice. Resistance and Hope, a collection of essays written by disabled activists and creatives, is no exception. Published in 2018, Wong conceptualised the idea for this collection in the aftermath of the 2016 United States presidential election, an event that commenced four years of slashing most of the progress the American disabled community had fought for. For many disabled people in the US, their very survival was at stake. The sixteen essays written by seventeen inimitable disabled people promises ‘crip wisdom for the people’, but it delivers so much more than that. As I hunched over on the carpeted floor of my bedroom reading their words glaring from a PDF on my laptop, I felt anger and sorrow, I felt joy, I felt the comfort of every single disabled body hugging me and each other, I felt powerful, and I felt so, so very alive. Having read this at the turn of the new year, in the last weeks of Trump’s presidency, I kept thinking about how, as a people, we survived. This is not to say that things will automatically get better, of course: several of the authors and myself share the opinion that there was nothing surprising about a Trump win, nothing shocking about the system that allowed for this to happen, that needs to be razed. But I was reminded as I read and learnt from these writers that we did resist, we did hope, and it is vital that we continue to do so.

Lydia X. Z. Brown starts the collection by discussing the importance of fighting for an equitable world while also challenging the ableist toxicity existing within many activist spaces that in disavowing imperfection often does not allow for growth. Acknowledging the varied experiences within the fight for the shared value of disability justice is the only way we can all get there together. Anita Cameron follows with a topical discussion on the importance of hope together with resistance: in the many ways marginalised groups have come together across the US and world, hope kept everyone going. Even in the darkest times, hope is not a foolish dream but rather vital in pushing for progress. The next essay is by Cyree Jarelle Johnson, who condemns the eugenicist rhetoric Donald Trump has been spouting about autism, children’s education and vaccines even before his presidency within the context of the rumours surrounding his son Barron being autistic. DJ Kuttin Kandi and Leroy Moore then walk us through the hxstory of Hip Hop music, resistance, love, and hope. They also discuss the continued marginalisation of disabled musicians within this space and highlight the talents of disabled Hip Hop artists such as Kase2 and the Krip-Hop Nation. Mari Kurisato’s contribution, a short but sweet manifesto entitled ‘They Had Names’, left me feeling like my heart had been wrenched out of me, but then put back in fortified with passion and resilience. She writes about the 2016 massacre of nineteen disabled care home residents in Sagamihara, Japan, and how the victims’ names were purposefully hidden, silencing their existence. Kurisato highlights how her Indigenous heritage influences her activism, and how we must resist and hope so that future generations of disabled people will remember that we exist, we did have names. Talila A. Lewis fights for prison abolition and encourages her readers to do the same for true justice, love, and liberation. Noemi Martinez discusses what survival means inside a multiply marginalised body, especially when pouring too much of herself into her communities to feel belonging. The next essay, by Stacey Milbern, talks about Medicaid cuts, the pros and cons of caregiving collectives, and mental health in disabled and queer communities of colour. This is followed by Mia Mingus’s writing on how protests against Trump’s 2017 Muslim ban encouraged her to envision a world where disabled people were truly valued, cared for, and felt like they belonged in society. Lev Mirov’s heartbreakingly hopeful essay on the experience of living in a disabled and chronically ill body with a lowered life expectancy, but feeling like life was stubbornly worth living nonetheless, got me that much closer to feeling the same – extra props since I love seeing other disabled medievalists doing fantastic work. Shain M. Neumeier analyses the pitted dichotomy of ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ disabled people espoused by the Trump administration. As is rightfully always discussed in these times, radical, hopeful self-care is championed by Naomi Ortiz. Furthering Neumeier’s discussion, Victoria Rodríguez-Roldán challenges the lack of inclusion of every kind of disabled person in the movement’s ‘nothing about us, without us’ slogan. Vilissa K. Thompson writes about the reception of her multiple marginalisations and ‘the audacity of hope in the Make America Great Again era’, pushing for unity, hope, and self-care in the face of oppression. Aleksei Valentín, Mirov’s spouse, discusses how his Jewish faith guides his activism through the principles of Kavanah and Tikkun Olam: we must engage in activism against the world’s pain and suffering with intention, but never give up when we are struggling or despairing. Last but not least, Maysoon Zayid censures the many attacks against disabled bodies carried out by Trump and his advisors and gives some great tips for engaging in political activism. Micah Bizant and Robin M. Eames helped put together this collection alongside Alice Wong; every single person behind the creation of these eighty-two pages is a force to be reckoned with.

For disabled readers of these essays, they feel like coming home, waking up, and winning a war. For non-disabled allies (and even, if not especially, those who do not support us), the collection is an invaluable insight into the fight against injustice which disabled people have been engaging with for decades simply for existing in our bodies. I truly have only good things to say about Resistance and Hope: no description I could come up with of its contributions is anywhere close to as powerful as they are. As America prepares itself for its next president, we must not forget all the disabled people who were killed by Trump’s policies, and we must remember to never stop resisting, and to never lose hope.

Alice Wong is the editor of another compilation of disabled stories entitled Disability Visibility. As you ride the empowering high these essays will bring, I suggest picking up this one next.

Mia Nicole Davies is a disability advocate and freelance writer currently writing for Mxogyny and various zines. They are also the LGBTQ+ Representative and University of Edinburgh ambassador for TABOU, a university student magazine increasing access and inclusion for disabled voices.